News

Dr Rebecca Montacute, Research and Policy Manager at the Sutton Trust, looks at the educational backgrounds of the new House of Commons.

Last week’s election saw big changes in Westminster, with almost a quarter of MPs either standing down or losing their seats. 155 of the 650 MPs who will take up their places on the green benches this week were not there when parliament broke up in November.

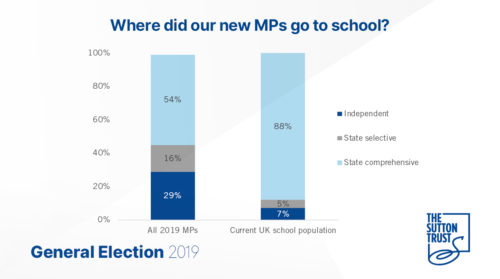

However, while there have been big political changes in the House of Commons, the educational background of the country’s MPs has stayed remarkably consistent. Before the election, 29% of MPs attended private school – four times higher than the rate in the general population. And after the election that figure hasn’t budged, still standing at 29%.

The proportion of MPs who attended a comprehensive school has however continued to go up, rising slightly to 54% from 52% in 2017. But as we have seen, this isn’t because of fewer MPs going to private schools, but rather due to a drop in those having attended grammars (14%), an ongoing trend that is unsurprising given far fewer students are now educated in selective schools.

Access to private school is heavily related to a family’s income. Only a small number of places (1%) qualify for full bursaries to cover fees, and only 4% have more than half their fees covered. This matters, because if MPs come from very different backgrounds to the general public, there is a risk that the concerns and priorities of all parts of society will not be adequately reflected in parliament. MPs are also ultimately responsible for national education policy, so it is concerning if a large number of MPs do not have experience of the state education system.

Are newly elected Conservative MPs more likely to be ‘working class’?

Much of the coverage over the weekend has focused on the incoming group of new Conservative MPs (e.g. Working-class MPs make the victory truly comprehensive). So, do new Conservative MPs really look different to returning MPs from the party?

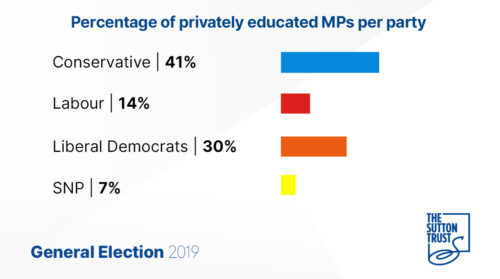

According to our analysis, the proportion of Conservative MPs educated at an independent school has indeed fallen, from 45% in the 2017 parliament to 41%. But there is a caveat to that data. While we found school background data for 93% of the 650 MPs in the new parliament, we were unable to find information on the school background of 1 in 5 of the new Conservative MPs. Given the scale of the difference between these new (28%) and returning (45%) Conservative MPs, it is likely that this fall in privately educated Conservative MPs is a genuine trend, but we can’t currently be certain how large that difference is.

With the privately educated so over-represented in politics, what can be done to level the playing field? Improving political education in comprehensive schools is a great place to start. While students at top independent schools like Eton, Winchester or Millfield (all of which returned several MPs each) have access to politics societies, debating clubs, and even visits from high profile MPs and political journalists, the same is not true in the average comprehensive school. Given that, it’s little surprise that 6% of our MPs come from just 10 independent schools.

To open up politics to all young people, opportunities to take part in extracurricular activities which develop essential life skills valued in politics, like public speaking and confidence should be expanded in state schools, and the provision of citizenship education should also be improved to create a better understanding of politics, democracy and government.

Another big barrier in politics are unpaid and unadvertised internships. Sutton Trust research has found that both are common in parliament, with almost a third (31%) of staffers working in Westminster having previously worked for an MP unpaid, and over a quarter (26%) gaining their role through a personal connection. These practices stop young people without money and connections from being able to access these opportunities. Given many MPs themselves start out working in an MP’s office, these positions are an important ladder into politics, and should be made accessible to individuals from all socio-economic backgrounds.

Before the election, the Sutton Trust’s CEO James Turner wrote to all candidates standing to become the next Speaker, asking them to commit to ending unpaid internships in parliament. We hope that the new speaker Lindsay Hoyle will take strong action on this issue, including asking the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority (IPSA) to review their policies, for example by considering whether funding levels for Westminster offices need to be increased to ensure that interns are paid, or whether additional ring-fenced funds should be given to MPs to pay interns in their office – as is now the case in the US.

Together, these changes – as well as others we have previously outlined – could make a real difference to opening-up politics, and ensuring that talented individuals can go on to represent us in Westminster, no matter what their background is.